Flood Boats

Floods are a common occurrence around Australia, but they occur in diverse environments and require different means to combat their effects on people living in their path. In some areas it’s a fast rising torrent passing through a relatively narrow path formed by hills and valleys, but in other locations it’s a gradual rise filling and flowing unchallenged over a vast saturated plain.

Coastal flooding appears to be more common in Australia, but that’s more to do with the majority of the country’s rivers flowing to the sea from nearby ranges. The fewer river systems in the inland are all subject to flooding when the right conditions prevail, and the Murray Darling System in the south east of the continent has had many significant occurrences.

Floods bring water beyond its normal boundaries so that it is covering areas otherwise traversed on land, and for decades the only access to support victims was by water. Only recently has support from the air been a realistic addition to emergency services, and often it works in tandem with waterborne actions.

Some of the earliest written reports of flooding rivers come from explorers and colonists moving out into the country and meeting the challenge with little warning or anticipation, and perhaps even less planning. In some instances they only managed through Aboriginals helping them by transporting the colonists across waterways with their own Indigenous watercraft. The Aboriginal people understood their environment and in many situations would be able to read the signs indicating a flood was possible. This would allow them to make preparations and secure their craft against the developing conditions, but it’s quite likely there were times and incidents when their watercraft were also lost.

As areas were settled by Europeans and they began to observe the cycles and patterns of the weather, they learnt the lessons of floods and, depending on the circumstances, planned ahead on how to survive them. Sometimes it was a private arrangement, but in other instances communities looked to authorities to provide the planning and support- what is known as infrastructure.

An early example of both is seen in the Shoalhaven district where as communities established in pockets around the rivers they were affected by flooding including a severe one in 18.. The NSW government responded with two craft purpose built for the area, but they were never used as they were considered too heavy for the task. When they fell into neglect and disrepair, local land owner David Berry and the Berry family responded and provided two craft and boathouses to replace the earlier ones.

Further north the Hunter River flooded regularly inland from the coast over low farmland and into towns, and councils provided flood relief with wooden craft. Maitland City Council provided craft located in different centres along the Hunter River and its tributaries. On the Clarence local volunteers manned a boat, a situation likely to be repeated on other big rivers along the northern coastline.

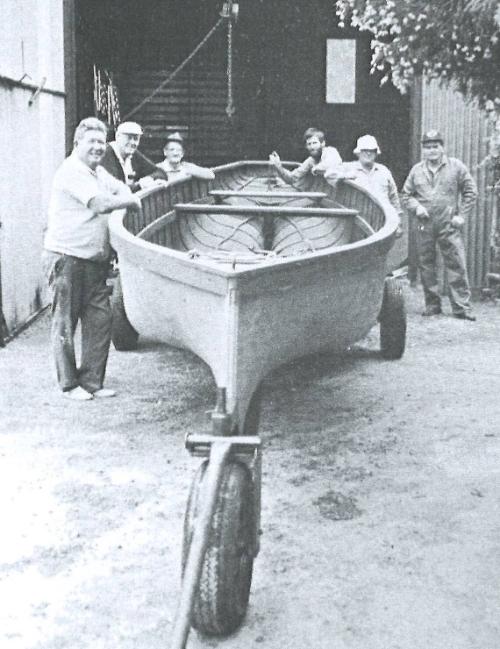

In all of these areas they used wooden, clinker construction craft, and were kept close to the river ready for use at short notice. They probably leaked a bit if they were not used a great deal, but once launched and in use over a few days quickly took up at the seams and became watertight. They were open skiffs along the lines of the waterman and butcher boats, their profile was often quite elegant with a rounded bow and raked transom stern. They were fitted out with four thwarts for the oarsman, a bow thwart, a stern thwart and stern side thwarts. There were floorboards and stretchers, and a rudder was common place too. Manoeuvrability in a long narrow boat is a challenge and made harder with fast flowing water and awkward, uncommon situations when rowing around buildings with street signs, poles and trees to avoid.

In contrast to the wooden boats, Queensland has number of examples of metal boats used in remote locations. The patterns and variations in the environment are more extreme, as were some of the locations and it made sense to use a metal boat. When the rains came it was often a monsoon replacing a long dry winter and spring, so a wooden craft would have dried out extensively and opened up at the seams, whereas a metal one remained secure. In addition, a common trade in the area was blacksmith who could fashion repairs quite easily without having to be a shipwright, and both circumstances were easily met with a metal- iron or early steel plate’s craft. The two craft located in the north at Coen and Mayfield probably spent a lot of time on hard ground beside a barely flowing creek in the dry heat, before being brought into action to bridge the now relatively wide crossing in what has become fast flowing river. It is thought they may have been assisted by being tethered to a wire trace between two trees or posts on either side so that they were not washed out of control downstream. Even so the rocky nature of the area put plenty of dents into the plating.

On private property inland, stations covered a huge area, and the floods when they came could cover much of this for an extended period cutting homesteads off from townships for weeks. Any stations had a simple craft to use on a river or lake if it was on their boundary, but they came into use with great significance in a flood. On the low flat land around the Darling River, Popilitah Station had a flat bottomed metal craft in the shed ready for occasional use. In big floods they marked the trees to help guide them across the land to a point where they could set off or town for supplies to see them through the couple of weeks when roads were covered or impassable.

Metal was a commonly used here, for similar reasons as in Queensland. It suited the dry environment, it was easy for local firms to make and easy for farmers to fix themselves. Milpara Station has two such craft, and one came from the Plumbing Division of the local fruit co-operative who made them as a stock item along with water tanks and other fabrications. Corrugated iron (or steel plate) was an easily available material which had some stiffness as a flat panel so it was an ideal material to form into a simple boat.

An alternate solution is seen in the Wagga Wagga district with CONRAE I and II. They were home built in wood from shelving material and mostly used for duck shooting and fishing, but when the Murrumbidgee flooded, they too took on a useful role helping out along the flooded streets. Many of these regional, amateur built craft shared similar characteristics- a flat bottom with no rocker, straight sides and other simplifications that would have brought problems in coastal waters. On the inland however the rivers and waterways were often much calmer, and the people using them were resourceful, capable and knew their craft’s limitations from experience, and kept out of trouble.

In more recent times, dinghies and surfboats were brought from the coast to the nearby hinterland to help out. In the 1950s, when a series of floods brought the Maitland and Hunter areas to a standstill, they took as many tinnies as possible from dealers to help out, powering slowly along streets in townships with water half way up the light poles and their wash lapping onto door way tops and shop awnings.

Two articles from Seacraft magazine in 1952 and 1953 demonstrate the government’s response to the floods in the early 1950s. The Public Works Department commissioned a plywood craft 7 metres long for use on the Hawkesbury, it was powered by an inboard petrol engine. In the western districts the NSW Police commissioned a much smaller 3 m long outboard powered craft, designed by a naval architect. In both instances the craft were very successful, and as noted they countered the situation where” Most authorities are only too happy to use the first type of boat available, which in the majority of cases proves to be inefficient and dangerous when called to a job for which it was never intended.”

Today emergency services are ready and waiting to move into action. They can have inflatables and other small craft trailed in with 4WDs, manned by trained crew with PFDs, hi-vis clothing and emergency equipment to engage in a coordinated rescue in difficult conditions. They can work with helicopters and when required, military support in the most severe situations. As the situation stabilises out come the locals with their tinnies, recreational kayaks and canoes to help support each other through the receding crisis.