18-Foot Skiff Class

1890 - 2011

There is much that is true in this broadly held conception, but it is a combination of different aspects. It is an evolving social story of a way of life for many people, an exciting example of highly skilled sailing, and a reflection of the changes in technology, factors that have all kept the class sailing for over century.

The 18-foot skiffs probably began as a formal class in the 1890s, and were in many respects a smaller version of their bigger relations the 22-foot and 24-foot half-deckers and open boats. These were the boats for the working class, the tradesmen of the foreshores. Their lifestyle afforded few luxuries, they were both proud and hardened to their manual tasks, and they shared many common bonds that saw them pitch in and support each other at work and as a social group. The skiffs reflected this, simple but robust craft, crewed by sailors already bonded by their background, working as a team. It was also an escape from the routine; over-rigged with a vast sail area, sailed on the edge with fierce rivalry, the skiffs were a weekly adventure that must have satisfied a desire to break away from the mundane weekly chores.

Walter Reeks, an English naval architect and yachtsman who settled in Sydney in 1885 aged 24, very quickly established himself at home with a strong allegiance to his new country and to Sydney Harbour. Writing in 1888 for the Illustrated Sydney News on Yachting and Sailing under the title 'Small Craft', his enthusiasm is unmistakable:

"Turning now from the majestic and graceful yacht to the slippery, quick motioned, excitement giving half deckers and open boats, we find them legion. They are a wonderful class of boats, and despite their faults we have reason to be proud of the boats themselves in the first place, and the amazing skill which they are the means of imparting to those who sail them, in the second Quickness of eye, agility of body, and strength of nerve, are necessary in the highest degree; and probably in no other community are those essentials to be good sailors more fully developed than amongst the small boat fraternity of Sydney harbour. Some of the rivers with heavy tides and short choppy seas in England and the very broad skimming dishes in America, go far to produce the hanging out 'into her' style of sailing; but in Sydney boys do as much sailing of that kind in a month as is done in other places in a year.

… The spectator sees something coming which impresses him that a five-tonners sails have got adrift and taken a jaunt on their own account, for as the thing approaches naught but sails and spars are visible, but when it is abreast of him, he beholds a boat just big enough to seat and float her crew, with a boom twice as long as herself, a gaff as long, a bowsprit about the same and mast as if all spars were added together ( such is the first impression) tearing up the foam and water… It is gone, but 'it passed so swift, scarce the eye could say that such a thing had been ' and he breathes again, and after ascertaining that he was awake and sober, realises that it was a real boat… and there are times even with them when a very good idea of having been born a bird can be obtained"

Clearly the excitement and wonder of the craft was something to behold, and Reeks was not alone in this observation. In 1891 the successful Sydney businessman and entrepreneur Mark Foy was one of a group of people who established the Sydney Flying Squadron for racing on the Harbour. The club was established for working class sailors sailing in open boats whose proportions and build still had close connections to their working craft origins. It was a complete contrast to the elite yacht clubs with their fine vessels, sailing uniforms and gentlemanly ways.

Foy was the first commodore and became the saviour and driving force behind the club in the early years. He was confident and brash, with a plan to create a spectacle for the public and sailors. He offered prize money as an enticement for the sailors, and planned the races so that they could be easily followed from the harbour shore, especially prime vantage points such as Bradley's Head. The craft had bold insignias on their sails visible to those onshore, and they started in a handicap procession to remove any time corrections at the finish, sailing a set triangular course. Anyone could tell what was happening and who was winning; it was the boat in front.

The SFS established a simple rule; to race with the club the boat could not be longer than 18 feet. At that length a simple, robust and affordable craft could be built, but that humble concept was spiced with the same oversized sail plan as seen on the bigger 22s and 24s. You had to be game to sail one. To support the large rig a big crew was carried, they were live ballast. Only a small foredeck and narrow side decks were accepted, creating a boat with virtually no margin for error, guaranteeing exciting sailing for the crew and spectators.

The reckless nature of the sailing captured sailors into the class and lured crowds to the shoreline, the regular Saturday 18-foot skiff races were a premier sporting event throughout the summer. Detailed reports were run in the daily media. It was followed on the water by a small fleet of chartered ferries, and immediately latched onto by the bookmakers, it didn't matter that gambling was illegal. This fuelled an already emotionally charged event with the tantalising prospect of a nice return on a small outlay, the spectators became punters and the gambling addiction ensured many would be back each week.

Even in these early days the skiffs did not go unnoticed out side of Australia. Dixon Kemp's 'Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing' (1895 edition) carries a short piece on the 'Sydney Boats,' reporting on the open boats from 8 feet to 24 feet in length. The tone of the piece written from an English perspective hovers between respect, admiration then alarm and disapproval.

" the universal system of measurement is length overall… The consequence is that a boat has developed which has great beam, little depth, immense sails and a large centreboard. Great numbers as crews are carried, the whole of whom sit up to windward, holding onto life-lines, and hang flat out over the water on the gunwale sills…. They habitually sail their boats with the lee gunwale 2 or 3 inches underwater… the skipper knows to a fraction of an inch how far his boat can heel before a luff becomes necessary…length for length there are no boats afloat which will hold these Sydney 'flat irons' in a light day. In running and reaching kites of every description are carried…Of course, capsizes, especially in gybing are very frequent….the writer has seen four 24 footers go 'into the ditch' one after the other in gybing round a particularly bad headland.

The objections to these skimming dishes are numerous. In a seaway they pound frightfully, and a Clyde 23 ft would do what she liked with them..… it is difficult to get a dozen or fifteen crews… no bulb keel idea seems to have caught on… and under the Sydney [handicap] system the boats at the end of the race are generally packed together within a few hundred yards, and bad luck will affect all equally. Probably this system will never be popular here."

That's one view , but then on the other hand the now well known solo sailor Captain Joshua Slocum had visited Sydney in 1896 and he liked what he saw: In his book he recalls:

" the typical Sydney boat is a handy sloop of great beam and enormous sail-carrying power, but a capsize is not uncommon for they carry sail like Vikings."

The analogy to the spirited and feared Vikings is appropriate. The racing was tough and gave rise to many stories of larrikin behaviour that parallel the Australian character developed by the European colonisers whose arrival in Sydney was barely 100 years beforehand. They had survived an unforgiving landscape with a combination of resilience, ingenuity and eventual understanding of the environment, and it hardened them to their life, forging a mixture mateship, loyalty and rivalry. The skiff sailors were the same. Loyal to each other, ready to sail in any conditions with different rigs to suit the conditions, aware from experience what the weather might do, and determined to sail as hard as they could.

Life as a crew was tough; bare hands and raw strength in uncomfortable conditions, crammed together with no space and now where to hide. The bailer boy had the worst of it; his initiation into the sport was spent in the bilge under the feet of his burly crew, trampled, abused and yelled at no matter what. If the breeze went light, sometimes crew were ordered overboard to swim ashore or wait on one of the islands or channel pile markers to be picked up later. Fights were said to be common place between crew and even within boats as tempers flared in tight situations. In the late 1920s ARLINE failed to give room at a mark to BRITANNIA, so BRITANNIA's crew tried to press ARLINE's boom underwater. ARLINE's crew of police and slaughterhouse workers retaliated, and one of the meatworkers started out along the boom with a knife in his mouth. BRITANNIA's crew then knocked him out by hurling a stone demijohn at him and ARLINE broke off the fight.

The established pattern of racing and the class remained virtually unchanged for almost four decades, despite the fact that the rules if they could be called that had few restrictions. The half decked boats remained wide and deep with solid cedar planked hulls, thwarts, a tabernacle, lee cloths, and a steel plate centreboard. They were pushed to the limit. The upwind sailplan was gaff rigged main, jib and tops'l, but downwind this was then overshadowed by a huge spinnaker set on a pole that was assembled in three sections, a ringtail hung off the leech of the main, perhaps a watersail pulled out under the boom and even a balloon jib. The hull disappeared under a cloud of canvas propped up by spars tensioned with iron rigging, all trimmed by manpower in a place where caution was often considered an anchor.

The 18 footers also took hold in Brisbane where they became well established on the Brisbane River, and to Western Australia for a brief period where they raced on the Swan River. Perth even held the Australian Championships in 1925 in a bid to promote the class in that state.

Nothing very significant happened to upset the status quo, the class sailed on through the early decades of the 20th century creating legends out of skippers such as Wee 'Georgie' Robinson and BRITANNIA , Chris Webb and AUSTRALIA, Peter Cowie and SCOT, Billy Fisher and his many AUSTRALIAs, Billy Dunn and KISMET. A couple of skippers tried a snub bow such as seen on Norm Blackman's YENDYS, but change was very gradual.

At the beginning of the 1930s change began to happen more quickly. Charlie Hayes built ARRAWATTA not only with a snub bow, but it had a new Marconi rig and a mainsail with battens to support more sail area. It won the Australian Championships in 1931. Soon after came the first big upset, and it was the beginning of a long period of controversy involving politics off the water.

In 1933 the Queenslanders launched ABERDARE. Built by Alf Whereat it had only seven feet beam and seven crew and could plane downwind easily. The skiff was virtually unbeatable, winning the Australian Championships on the Brisbane River for the 1933/34 season. It won again in Sydney in the following season, and over five seasons won the championship four times. In 1936 during a gale it was timed at 23 knots during a ¼ mile run on Brisbane River. Most Sydney crews were horrified at this radical change in proportions, and the traditional skiff sailors condemned it as a freak. They felt ABERDARE and its sisters would destroy the sight of the wide 18s with huge sail plans and their big crews.

However Sydney skipper Bob Cuneo saw things differently and commissioned a similar hull for the next season, which he called THE MISTAKE, and carried the sail insignia 2+2=5. The club moved to ban the boat unless it sailed with at least 10 crew members. In 1935 they went a step further banning boats with a beam of 7 feet or less and withdrew from interstate racing.

This caused a split amongst sailors and club officials in Sydney and Brisbane, The SFS and Brisbane 18 Footer Squadron placed restrictions on the dimensions to try and retain the traditional type, but the Brisbane 18 Foot Sailing Club and newly formed NSW 18 Foot Sailing League fostered the new or modern type.

In a sense history then repeated itself; once again a confident and strong personalty took a lead role in establishing a new way of doing things. The clubs founder and first president was sporting promoter JJ Giltinan, a former member of the SFS and the man who had begun the breakaway Rugby League code early in the 1900s. The League raced on Sundays, and forged ahead to secure the higher ground by creating a World Championship event between skiffs raced in Sydney, Queensland and WA, and similar 18 foot long boats raced in Auckland New Zealand. It was first won by TAREE sailed by Bert Swinbourne and built in Brisbane by Norman Wright.

Crowds still flocked to watch the 18s on both days, and the League enticed some of the SFS boats to race on Sundays with special, handicaps. The rift between the two clubs was enormous and took decades before it was considered healed. For many years the SFS tried to maintain the old traditions more or less alone, leaving the League to continue down a new path.

Despite the onshore club arguments it was still a spectacle for the public and the crews, described with some awe in the American magazine Rudder September 1938 in a report written by visiting American cruising yachtsmen Ray Kauffman and Gerry Mefferd.

'On Sundays, before a floating gallery of nearly 10,000 spectators, the famous 18-footers race. Countless small craft line the course and half a dozen big ferries, crowded and complete with book-makers, worry along among them. It is an exciting race and the skippers, eager to press their boats to the utmost, crowd on incredible amounts of sail. And it is this craze for sail that makes this sport so exciting and the outcome of the race uncertain right up to the final gun. In too many cases the leading boat, driven to the limit, has caught a sudden gust of wind and capsized.

One of the most vivid glimpses we had of the eighten-footers was from the speedboat of a news cameraman who braved the profanity of the crews and darted right alongside the boats for close-up action shots. At the more exciting moments of the race, it was fascinating to see the well trained crews handle, in the confined space of an eighteen foot open boat, enough gear to sail a full blown ship.'

Development continued until racing was halted during World War II, but picked up again after the war. The boats became narrower and ended up at six feet beam. Moulded construction was introduced and gradually more modern materials were adopted for rigging, sheets and sails. Crew began to use trapezes to stand out from the hull. Speed was increasing and whilst they were a step ahead of the traditional 1920s style, they were still large and relatively heavy compared to new lightweight dinghy designs from Europe. This international influence was to create the next major upset.

In 1959 Bob Miller and his crew, Norman Wright III and Jack Hamilton built TAIPAN to Bob's design, it was perhaps the most revolutionary craft in the class history. This Queensland craft was very lightweight, built in plywood, had a single chine hull shape, only three crew, and an overlapping genoa. It could plane upwind which was a major breakthrough, and it bore no resemblance to the typical skiff of the period. Although it failed to win the World Championships due to gear failure and other errors, it was clearly the fastest craft and pointed to a new direction forward.

Once again the change was resisted strongly in NSW, but there were also a large number who could see the advantages of the cheaper and lighter craft, and started to build boats of this type. Reversing the previous situation, the SFS was first to accept the new three handed type, but even then not all members supported this move.

TAIPAN was followed by Miller's design VENOM, which won the 1961 World Championship series, and although Miller's pair of boats pointed clearly where the class should go, many clubs had difficulty in accepting such huge changes in one go. The class became fractured with the NSW clubs having different rules and restrictions which allowed some of the new features but not all at once. Many boats had four or five hands but were considerably lighter, many boats raced with SFS on Sunday and then carried more crew to race with the League on Sunday.

From the 1950s onwards sponsors began to help with some support for the craft and had their logo on the sail as the emblem. The 1960s became a period of significant change that was partially restrained by the arguments between and within clubs.

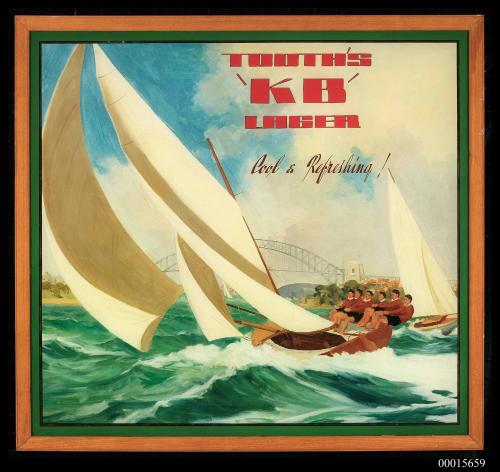

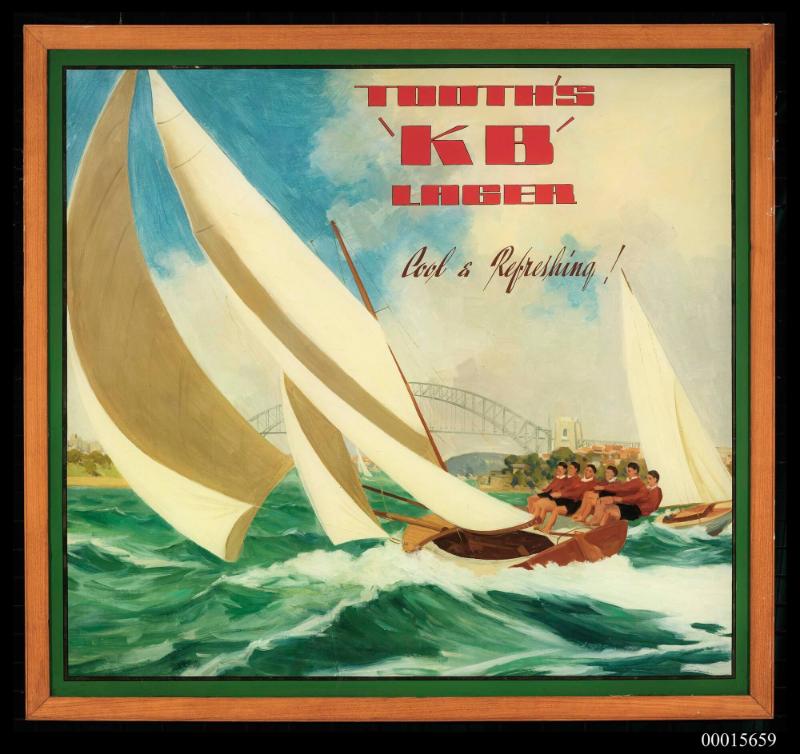

In the 1970s where there was a rapid development of hulls and rigs. New Zealander Bruce Farr was one of the principle designers, refining his craft each year to make them lighter and faster. Three crew became universally accepted, and the craft began to get wider with small wings at the gunwale to give the crew greater leverage. Some buoyancy was permitted, but to retain some respect for tradition if you capsized and the mast touched the water you were disqualified. TRAVLODGE sailed by Bob Holmes and then Dave Porter's KB were dominant craft during this period, which also showed the trend to stronger sponsor support. The clubs were more or less reconciled and sailed to the same rules, but the move away from the working class background which probably began in the 1960s was now well and truly exposed, and the class was at the beginning of a period when the sheer excitement of the sailing was largely supporting its existence its development aspect was controling the class direction.

By the end of the decade Iain Murray had adopted space-age lightweight, composite materials after one season in a plywood craft, and his almost total dominance with the COLOR 7 series of craft shifted construction to a new level of sophistication and evolution. He brought a professional sailing approach to the class, and as the 18-foot skiffs moved into the 1980s the boat had become a major campaign and was expensive to own and sail. Significant sponsorship was a prime requirement to maintain a position at the front of the fleet with an up-to-date competitive craft. COLOR 7 was joined by LYSAGHT COLORBOND, WRIGLEYS PK GUM, CHESTY BOND, PRUDENTIAL INSURNACE, STUBBIES and other well known brands. They had their name on a sail and it was matched with a significant outlay to support the design, construction and a seasons sailing for a craft carrying three complete rigs, a custom trailer and even a paid hand to work on it during the week. Last year's boat reappeared in a new guise for someone with much more limited funds, but this year's boat was always better so the race was already partially won if you secured a good sponsor.

The technical change that pushed things to a new extreme was the introduction of aluminium and mesh wings beyond the gunwale extensions. Richard Court from WA (where the craft were once again sailing) surprised the fleet with a set of wing extensions. Although fast, he could not quite catch COLOR 7. However the idea was quickly copied and immediately bettered, width grew rapidly until the boats were as wide as they were long. Rigs got bigger as well, speed was hitting new heights and they just looked unbelievable compared to anything else. The final refinement was a fixed spinnaker pole on the centreline with an asymmetric spinnaker, making the boat easier to gybe. Width grew again until craft had reached 26 feet from wing to wing. Julian Bethwaite had done his numbers and for three seasons he raced PRIME COMPUTERS, a successful two handed skiff. It was a giant 12 footer in some ways, but although good in light to moderate conditions, the power of three crew kept the three-handers on top.

Things boiled over in the second half of the 1980s, sponsorship ran dry and the class was in crisis. The fleet soldered on without any new craft for a season and then once again a saviour moved in.

Bill McCartney from the NSW League organised a package for sponsorships, events and media rights. In the 1990s his Grand Prix sailing was a modern Mark Foy enterprise and saw the craft organised to race in locations around Australia and even overseas, and it was filmed for TV. The teams were not just Australian, there were sailors from the US, New Zealand and the UK. To try and rein in costs the class adopted a reduced sailplan, reduced beam, introduced a number of maximum and minimum dimensions and basically became a one design class only allowing hulls to be built from one particular mould.

The focus was now the NSW League club, the SFS survived with a fleet of older craft and at the end of the decade had established a another parallel fleet of replica 18s which campaigned a mixed fleet of boats based on designs from the 1920s tup to the 1950s.

In 2009 this situation had stabilized with a core of modern 18s racing from the NSW Leagues club using one design hulls, rig restrictions and sponsors organised through the class management . On Saturdays the SFS sails a smaller fleet of modern 18s and growing fleet of replica's such as BRITTANNIA, YENDYS, ABEDARE, ALRUTH and others. One tradition remains in place, albeit on a much smaller scale, a ferry from the Rosman Fleet is chartered each weekend for spectators.

It is no longer the pride of the working class, but the 18-foot skiff is still seen as an icon of Sydney Harbour and retains its place as one of the most challenging and fastest dinghy designs racing anywhere in the world.

Person & vessel typeVessel class