Paddle Steamers of the Murray-Darling

The waters of the Murray-Darling trickle along some 13,000 kilometres of river, dispersing like veins over 400,000 square miles of Australian landscape. This substantial river system’s own long history speaks of rough geological fits and spurts, of a great continent turning slowly in its sleep and of the filtered snow of far distant mountain ranges.

Throughout the history of European settlement the Murray-Darling has been the subject of fierce debate over water usage and subsequent environmental damage. However life along its riverbanks, as Australia pivoted on Federation, created a unique waterside community whose legacy encompasses economic development and questions of national identity.

The Murray-Darling river system extends through much of south eastern Australia and its winding channels run across parts of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory. This river system had sustained Indigenous communities for thousands of years before European explorers began investigating the waterways in the 1820s.

Industry soon followed, beginning in earnest with the first two paddle steamers to reach Swan Hill on the Murray River in 1853 – Francis Cadell’s Lady Augusta and William Randell’s Mary Ann. The two men were spurred by the desire to find an alternative to the slow-moving and expensive bullock teams who were previously relied upon to transport produce such as wool and wheat from the isolated stations that peppered the Murray-Darling Basin.

Cadell and Randell’s efforts proved that the rivers were navigable and it did not take long for a growing fleet of steamers to become the life-line of settlers along the Murray-River Basin. By 1890 there were at least 170 steamers in operation, working the 5,600 kilometres of the Murray-Darling that was navigable. The shallow-draught steamers and their barges transported produce to the sea and rail ports of larger towns such as Goolwa in South Australia and Euchuca in Victoria, however they also returned with supplies for the settlers, bringing in tools, household goods, building materials and food.

A unique floating community developed along the rivers as the paddle steamers moved along the Murray-Darling’s waters. Residents eagerly awaited the arrival of the steamers, bringing news, household goods, medical supplies and staff to isolated homesteads and camps along the river banks. Steamers also carried tourists and often served as hotels moored alongside river towns too small to have their own. The paddle steamer Platypus, operating in the 1880s, included among its crew a team of women and their sewing machines who took orders at posts along the river before delivering the completed products on the return trip. The mission steamers Etona and Glad Tidings provided a mobile place of worship, bringing religion to remote regions unable to support a church.

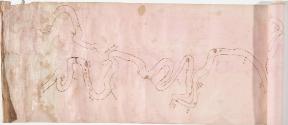

Ship-building industries developed alongside agricultural industries in towns such as Goolwa, Mannum and Moama and mariners and maritime tradesmen came from afar to exploit the burgeoning river trade. Skilled captains were required to navigate the Murray-Darling’s waters, which held many dangers of its own including hidden banks, snags and temperamental water levels. Navigational charts were often inherited, copied or created from an intimate knowledge of the river’s features. Several of these long hand-drawn scrolls still survive and they are as individual as their creators - often carrying inky representations of long-lost homesteads, structures and even prominent trees.

Into this world of river trade, the Sydney Morning Herald sent novice journalist Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean, to provide regular reports on rural developments. Bean would go on to become one of Australia’s most significant historians and later in life admitted to being unenthusiastic about the assignment, however his indifference was not to last. Bean’s initial weekly reports were compiled and published under the title Along the Wool Track which inspired a second journey, undertaken on a paddle steamer along the Darling River. This assignment also generated a book, Dreadnought of the Darling, which was published in 1911 and playfully referenced, in its title, the recently launched and head-line grabbing Royal Navy battleship. Dreadnought of the Darling contained accounts of daily life on a cargo paddle steamer, historical and geological observations and – most significantly – warm recollections of the characters Bean encountered.

When one looked again, she did remind one distantly of a warship of sorts… (p20)

Travelling on the steamer Janda (always referred to in the book as the ‘Dreadnought’) Bean wound his way into isolated pockets of the country where he met cameleers, boundary riders, station owners and shearers. He encountered Australians of all skills, backgrounds and vocations who were generating a living along the river and who, in his eyes, shared certain noble characteristics. The sum of his observations was that Britain’s colonial outpost was fast developing a nation of strong, resourceful and above all honourable people who exhibited a strong sense of loyalty Bean defined as ‘mateship’. In Bean’s eyes, the most important product of the rural industries along the river was not the material goods, but the men who were developing from its exertions.

One may just say this… if ever a certain ancient country, the old friend and protector of a younger land, finds herself in difficulties, there is a younger land, existing in quite unsuspected quarters… the quality of sticking – whatever may come and whatever may be the end of it – to an old mate’. p 312

Several years after Dreadnought on the Darling was published, Bean found himself observing Australians in far different context. In 1914 he secured the job as Australia’s official war correspondent, a position won narrowly from Keith Murdoch. Soon after Bean was reporting from the trenches at Gallipoli where he witnessed what he had hoped to see – that those qualities he had observed in the people of the Australian bush were coming to the fore in the crucible of war.

The big thing in the war for Australia was the discovery of the character of Australian men. It was character which rushed the hills at Gallipoli and held on there. (C.E.W. Bean: In Your Hands, Australians 1919)

Bean’s reports as a war correspondent echo his earlier rural reporting and leave no doubt about the admiration in which he held the average Australian ‘digger’. This veneration gave rise to the notion of the ‘Anzac Spirit’ and influenced much of Bean’s later work, including the extensive Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1818 and his establishment of the Australian War Memorial.

Bean’s attempts to define an Australian ‘character’ as he saw it emerge through the national experience of war had its basis in the rural communities along the Darling River. Bean, like Banjo Paterson before him, was inspired by the Australian bush in his search for a definable national identity - one that perhaps remains elusive, evolving and undefinable today.

The age of the paddle steamer on the Murray-Darling river system came to an end in the 1950s. many of the paddle steamers such as Lady Augusta to Etona and Bean’s Janda slowly disappeared from the water. Gone with them were the red river gums along the banks, sacrificed as boat-building material and fuel for engines. Produce instead came to be transported on railways and the river system itself continued on as a vital resource, although less as a highway and more as a disputed source of irrigation.

The era of the paddle steamers along the Murray-Darling left a lasting historical legacy, both economically and environmentally. But perhaps, as Bean suggested, the greatest legacy of this era was the people themselves - whose unique lifestyles became the basis of a national legend, legends that come to life board the few existing craft with some now operating as tourist excursion vessels.

Person & vessel typeVessel type